[CHECK AGAINST DELIVERY]

The evolution of NPLs in Europe: regulatory perspective and market developments[1]

Naples, NPL Conference

Ladies and Gentlemen, good morning.

I thank the organisers for inviting the Single Resolution Board, and myself in particular, to this important conference on The proactive management of Non-Performing Loans. Indeed, it is a relevant topic not only for supervisors, but also for resolution authorities. At the SRB, our goal is to ensure that each bank under our remit can be orderly resolved, safeguarding financial stability and protecting taxpayer’s money.

In my intervention, I will first provide an overview on how the NPL challenges have been addressed at EU level after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) as well as the importance of their monitoring also from the perspective of resolution authorities; then I will turn to the recent trends of the NPLs, the growth outlook and the latest financial market developments.

The regulatory response to high NPLs and market initiatives

Asset quality issues and the policy need to deal with NPLs for the purposes of financial stability and economic growth became particularly acute in the aftermath of the GFC. Whereas NPL ratios stood at manageable levels prior to 2008, the crisis brought an unprecedented economic shock to the balance sheet of lenders. At the same time, that crisis highlighted structural reasons that limited the capacity of large parts of the euro area’s banking system to deal with distressed debt.

The level of NPLs in the euro area reached around 8 % in 2014, which is the highest level reported since the sovereign crisis. NPLs amounting to almost euro 1 trillion had piled up in the balance sheet of significant banks in the euro area. Also in consequence of high levels of NPLs, banks’ profitability and their capacity to provide lending to the real economy remained subdued for a number of years.

Policy initiatives have played a key role in pushing banks to clean up their balance sheets. I will summarise the main initiatives undertaken here below, while in paragraph 3 I will illustrate where we stand today.

The EU regulatory and supervisory response to the NPL challenge rising from the financial crisis started with the intense action exercised by the ECB-SSM together with that one of national authorities, the guidelines issued by the EBA[2], the change in the accounting practices for loan loss provisions and the launch of a comprehensive Council Action Plan on NPL[3] in 2017.

The Council Action Plan consisted of an EU-wide package of policy measures aimed at reducing existing NPLs as well as preventing the build-up of new distressed assets. The action plan proposed regulatory measures in three areas: on supervision, on the development of secondary markets, and on the reform of insolvency frameworks. As of 2019, most of the measures proposed by the Action Plan have been implemented (12 out of 14), although a number of them require ongoing efforts to achieve their intended outcomes.[4]

The SSM approach included strategic elements focused on addressing legacy NPLs and aimed at limiting the build-up of new NPLs in the future. It consisted of an NPL Guidance to banks on non-performing loans published in March 2017; an Addendum to the Guidance, published in March 2018, which set out supervisory expectations for prudential provisioning for new NPEs, as well as supervisory expectations for the provisioning of NPE stock, as communicated in a press release issued on July 2018. The Guidance was later adjusted, in consequence of the introduction by the European legislation of rules on minimum loss coverage for NPLs (see infra)[5]. The SSM also provided guidance to banks on credit risk management during the pandemic period, through various letters addressed to the CEOs of credit institutions[6]. The harmonisation of supervisory practices and comparisons of NPL ratios across jurisdictions was facilitated by the EBA guidance on the management of non-performing and forborne exposures and their disclosures[7].

The accounting regime concerning loan loss provisioning has been revised in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, where IAS39 has been replaced by IFRS 9. The previous regime according to which provisions were based on the concept of incurred losses (backward-looking approach) has been substituted by that one based on the expected losses (forward-looking approach). This approach pursues a fuller and more timely recognition of credit losses. In the context of the changes to the Capital Requirement Regulation and Directive, the banking system was granted a transition period to smoothen the effects of the accounting change on capital.

In 2019, the prudential backstop regulation[8] was adopted, requiring banks to cover their newly-originated loans becoming NPLs with time-bound and minimum provisions according to a uniform calendar (so called calendar provisioning). In this framework, a capital deduction applies when provisions fall short.[9] The backstop is probably the main regulatory initiative to prevent the under-provisioning of NPLs. According to the EBA guidelines, banks with significant NPL levels also need to set out clear reduction targets and plans, as well as to have governance structures and arrangements to execute such plans effectively (either through sales, securitisation, or internal workout).[10]

On secondary markets, the sales and securitisation of NPLs were a key driver of their reduction in Member states with high non-performing loans, although bottlenecks and inefficiencies remain. EU regulators have tried to address the main obstacles to deep and liquid secondary markets, namely information asymmetries, barriers to entry, and limited number of investors. First, securitisation rules have been amended to cater for the special features of NPL.[11] In some European countries they had an important role to clean up banks’ balance sheets – also with the help of government guarantees. In the Banking Union securitisations of non-performing loans reached 60 bln. in notional volume in 2021. Second, although NPLs are already sold on a cross-border basis, their purchase and servicing mostly occur through local subsidiaries or branches, hindering EU-wide investments. The new Directive on Credit Servicers and Purchasers[12], which entered into force in 2021 and will have to be transposed by EU countries by the end of this year, introduces the regulation and supervisions of credit servicers, including a regulatory passport to operate across the EU, while ensuring a consistent level of consumer protection. The latter point is important since the Directive also applies to NPLs of retail consumers, who deserve to be protected consistently and with high standards in the entire EU.

Third, the EBA developed a data template for the information to be exchanged by buyers and sellers to reduce information asymmetries and increase the effectiveness of secondary markets for NPLs. Compared to the first templates, the EBA followed a proportionate approach, reducing the data fields from 200 to 130 (69 of which are mandatory).[13] The new data template approved by the EBA is expected to be endorsed by the Commission in the form of an Implementing Technical Standard (ITS) in 2023, and it will apply to loans originating after 1 July 2018. Although the template is mandatory, there is no enforcement mechanism to monitor its use. Nevertheless, investors and transaction platforms are expected to demand banks to fill the template as a pre-condition to buy or transact in NPLs. In other words, compliance should be mainly market-based.

EU regulators also discussed the opportunity to establish European NPL electronic platforms. Although no EU platform was eventually set up, the ideas shared by the Commission in its 2018 Staff Working Paper[14] facilitated the development of a number of private platforms offering pan-European services. Overall, the development of secondary markets requires the combined effort of all the interested market actors (banks, purchasers, services, electronic platforms). Events like today’s conference are therefore particularly useful as they bring all these different market participants together to discuss best practises.

Finally, Asset Management Companies (AMCs) and Asset-Protection Schemes (APSs)may be useful NPL management tools. This was also one of the main take-away of the European Commission 2020 Action Plan[15] – which was elaborated in consequence of the pandemic shock and reviewed the 2017 Plan with more tailor made and specific objectives. It proposed a series of actions to prevent the build-up of NPLs during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. AMCs can exploit economies of scale and coordinate creditors at a higher level, especially when the following conditions apply: first, there are high levels of NPLs in the banking sector; second, the NPLs are mostly secured by commercial real estate and large corporate exposures.[16] For example, in the aftermath of the GFC of 2007-09 and the sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12 AMCs played an important role in managing NPLs in a number of countries[17]. In the end, a European AMC or a network of AMCs have not been created,[18] however government supported schemes offering guarantees on large tranches of NPL debt have shown to be key drivers to reduce NPL ratios in countries like Italy (GACS) and Greece (Hercules). Public intervention, either via AMCs or APSs, increases the liquidity and depth of NPL secondary markets, encouraging private investors to participate. However, these interventions need to comply with the EU state-aid and resolution frameworks to minimize competition imbalances and protect tax-payers’ money. This implies that public guarantees as well as NPL transfers to an AMC must be priced at the Estimated Market Value (EMV) of the underlying assets, namely the same price that it would be paid by a private investor.[19]

Reforming insolvency and debt recovery frameworks is perhaps one of the most important elements to tackle NPLs.Inefficient legal enforcement and judicial backlogs are often cited for the slower pace of NPL reduction in a number of Member States.Unfortunately, here the progress appears to be more limited than in other areas, due to the legal obstacles to harmonize non-bank insolvency frameworks across the EU. For example, the EBA report on the benchmarking of national loan enforcement frameworks found “significant variability across Member States in the effectiveness of national insolvency practices as measured by recovery rates, time of recovery and costs of recovery”. As long as recovery times and processes will show strong differences across the EU, NPL secondary markets will remain prevalently national rather than European. Here Member States with slower recovery rates are encouraged to use the opportunity offered by the Recovery and Resilience Facility to upgrade their insolvency and debt recovery frameworks.

NPLs and crisis management

There is extensive evidence that a high level of NPLs is common in insolvency crises. As NPLs can have a major impact on a bank’s soundness, the first line of defence is represented by sound management of risks by the bank itself; in turn, supervisory authorities closely monitor the asset quality of banks and assess whether adopted practices are appropriate for the management of risks and of non-performing exposures. The work of supervisory and resolution authorities is highly complementary and in principle seamless in case of banks’ crises. A strong cooperation between authorities, based on extensive information sharing including on early warning indicators of potential banks’ distress, allows to manage banks’ crises in the most efficient way, safeguarding financial stability and protecting the taxpayers. The Memorandum of Understanding between the SRB and the ECB-SSM, lastly updated at the end of 2022, is a good example of the cooperation in place at Banking Union level between supervisory and resolution authorities.

As regards in particular the SRB, its responsibilities are resolution planning, resolvability assessment in peace time and crisis-execution at the moment of failure. Before resolution, high NPL levels may have a potential impact on the compliance of banks with the Minimum Requirement for own funds and Eligible Liabilities (MREL). MREL is a crucial element in the resolvability of a bank. One of the MREL metrics is expressed in percentage of total risk exposure, therefore its level is also affected by high risk weighted assets such as NPLs. The quality of the loan book may also influence the choice of the most appropriate resolution tool during resolution planning. For example, in the case of a transfer of assets, the SRB has to carefully identify the perimeter of assets - taking account of NPLs - that will have to be transferred to a purchasing bank or remain in the legacy entity to be wound down. The perimeter of assets of the bank is unlikely to remain static, and this includes the evolution of NPL portfolios.

The quality of the loan portfolio comes into play at the time of the determination that a bank is failing or likely to fail. The initial valuation should accurately examine the value of the bank’s loan book. A high proportion of non-performing assets is a source of major uncertainty, and estimating their recovery value is challenging. Likewise, some categories of these assets cannot be easily sold without a substantive loss of value, particularly in times of crisis. All of these factors materially affect the determination of a prudent and accurate value of the business.

The SRB has a variety of tools available for resolving a bank, but for a failing bank that has significant amount of NPLs in its balance sheet, one of the options to be pursued could be the Asset Separation Tool (AST), to be always used in conjunction with another tool. The aim is to effectively separate the distressed assets of the bank from the good part of the business, trying to avoid resorting to fire sales. The AST can be used to isolate NPLs of the failed entity and put them into an Asset Management Vehicle (AMV) where they can be managed as efficiently as possible. The AMV will manage the transferred assets with a view to maximising their value through an eventual sale or orderly wind down. An important aspect to consider will be how the AMV will be funded. If the tool is used in combination with the bail-in tool, the SRB will need to consider a prudent estimate of its capital needs. The SRB can also rely on the use of the Single Resolution Fund – provided a minimum bail-in equivalent to 8% of total liabilities including own funds is performed - to make contributions to a bridge institution or an AMV,to ensure an adequate level of capitalisation and liquidity, as the transfer of NPLs to an AMV will likely create significant costs.

The evolution of NPLs

Since 2014, the average ratio of NPLs in the EU started decreasing, yet at an uneven pace across European countries and banks. During the pandemic, the regulatory flexibility associated to COVID-19-related measures, such as loan moratoria and Public Guarantee Schemes, was used extensively by banks. In addition, the coordinated European response put in place by the authorities in order to maintain a level-playing field, paved the way for an overall solid post-pandemic recovery.

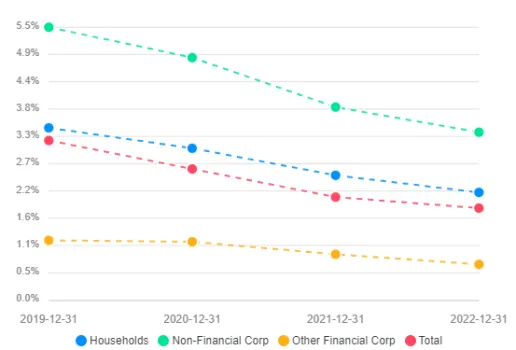

The NPLs ratio continued decreasing since 2014; in December 2022, according to the latest EBA figures[20], EU banks showed a ratio of NPLs of 1.8% of total loans[21]. For the sample of 100 Banking Union considered, the ratio declined from 3.2% at the end of 2019 to the EU average (Figure 1).Looking at the different categories of borrowers, the reduction was more intense for non-financial corporates, nevertheless the decrease was broad based for every category of borrower. It is noticeable that in the aftermath of the pandemic the ratio continued to decrease, also thanks to the public extraordinary measures assumed by EU governments.

Figure 1: Non-Performing Loans ratio20, % of Total Loans (Source: Finrep, 104 financial institutions)

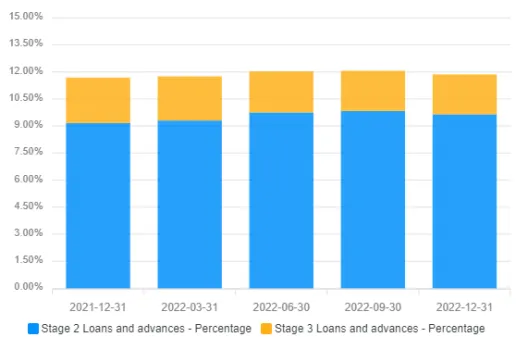

If the overall picture looks reassuring, attention has also to be placed to the signals of potential future deterioration. In particular, authorities monitor also underperforming loans, or “stage 2 loans” in accounting terms, that is, credit exposures whose risk has increased significantly since origination but are not considered impaired[22]. Since the beginning of 2022, we have observed a constant increase of stage 2 loans, which in Q3 2022 reached 9,8% of the total loans, and in Q4 have slightly decreased to 9.6% (figure 2). Higher stage 2 loan inflows might signal increasing NPL volumes in the near term, once extraordinary NPL transfer operations (sales and securitisations) slow down.

Figure 2: Stage 2 and stage 3 loans, % of Total Loans and Advances (Source: Finrep)

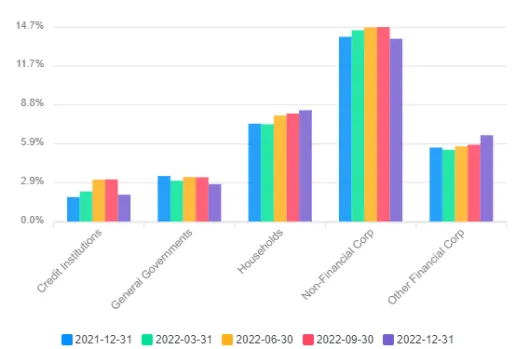

Looking at the breakdown by portfolio, we find that in the first 3 quarters of 2022 the stage 2 ratio increased for all the main categories of borrowers (figure 3). In Q4 2022 we instead notice an increase of allocation to stage 2 only for loans to households and other financial corporations.

Figure 3: Share of stage 2 loans by portfolio, % of Total Loans and Advances (Source: Finrep)

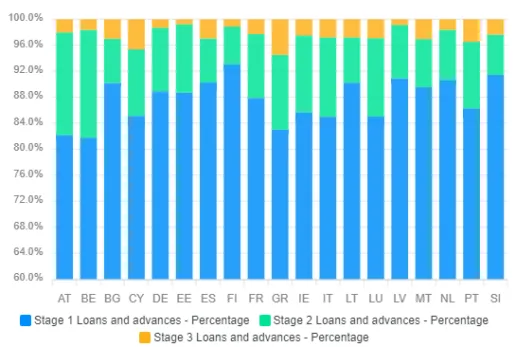

Looking at the distribution by countries, we see a heterogeneous distribution of stage 2 loans across different member states, ranging from 16% in Belgium, to 5.8% in Finland (figure 4). In the majority of countries, loans to non-financial corporates show the highest stage 2 ratio.

Figure 4: Loans stage allocation by country, Q4-22, % of Total Loans and Advances (Finrep)

Growth outlook, recent financial market turmoil and loan quality

Following the pandemic crisis and the macroeconomic events associated to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, an inflation shock has emerged and has gained strong momentum in 2022, due to both supply-and demand-side factors. The post-pandemic recovery has slowed down, and this new shock has been gradually producing its impact on the economy since the last months of 2022. According to the March 2023 ECB baseline forecast, the euro area economy will grow by 1.0% in 2023 and by 1.6% in 2024. The ECB macroeconomic projections were finalised before the recent financial market turmoil, which may imply additional uncertainty around the growth outlook. The ECB projections are broadly in line with those released by the IMF earlier this month, which foresee the euro area economy to grow by 0.8% in 2013 and by 1.4% in 2014.

As regards the recent financial market turmoil, in the US we have witnessed the failure of three mid-sized banks, among which Silicon Valley Bank, and in Switzerland to the crisis of Credit Suisse which has in the end been merged with UBS. In the failure of SVB the trigger was not the level of NPL, rather a peculiar and extreme business model – which does not find a parallel in the European banking sector - in a situation of rapid increase of interest rates and weak application of prudential rules with respect to international standards. For CS there had been a long series of difficulties, lack of confidence in the business model which in the heightened market uncertainty determined by the failure of SVB triggered a severe liquidity crisis. Market volatility increased abruptly in March, with main equity and banking sector indexes marking notable losses. We also observed a general increase in funding costs for banks following the write-down of AT1 bondholders. On the whole, there was limited direct and indirect contagion for EU banks. The recent crises have showed us, once again, that viability of business models, sound risk management, transparency and regulatory compliance are fundamental elements of a healthy banking system. These events have also triggered some reflections in the international regulatory community in order to draw lessons for the prudential and resolution framework.

The EU banking sector has shown resilience until now, with robust levels of capital and liquidity. Capital ratios of European banks are much higher than fifteen years ago, with CET1 ratio equal to 15.5% at end-December 2022. On a similar note, the liquidity position is robust and large parts of liquidity buffers consist of cash and deposits with the central banks. Also as result of the net effect of higher interest rates, banking sector profitability (ROE) has increased to its highest level since 2014, reaching on average around 10% in the BU at the end of 2022.

Going forward, there are a number of factors that are expected to weigh on the outlook for European banks. In particular, the deceleration of economic growth and high interest rate environment may lead to a deterioration in asset quality. Loan growth has stopped in the last quarter of 2022, for both households and corporates. Higher interest rates, lower consumer and business confidence and high energy prices drove lower demand for loans, while the lower banks’ appetite for risk determined a tightening of credit standards. This situation will likely have adverse effects on borrowers. The impact is likely to be heterogeneous across sectors and countries, and it will depend on factors such as energy dependence and the prevalence of floating rate lending.

Conclusions

Let me conclude by saying that the European banking sector has considerably improved NPL ratios, which are relatively low and stable now. The positive trend has benefitted from a number of initiatives undertaken by EU and national authorities.

The European banking system has shown a remarkable degree of resilience, thanks also to the high levels of capital and liquidity induced by the regulatory reforms undertaken after the Global Financial Crisis. However, we have also remarked an increase of Stage 2 allocations. In addition, an environment of weak economic growth, still high inflation and rapidly increasing rates, coupled with macroeconomic uncertainty, is bound to have an effect on banks’ balance sheets. In times of uncertainty, there is therefore no time for complacency, but rather for vigilance. We encourage banking institutions to continue adopting prudent practices in the supply of loans and the management of credit risk, thus preventing the deterioration of its quality.

Thank you for your attention.

[1] I would like to thank Shady Abd El Kader, Riccardo De Bosio, Giacomo Massa and Francesco Pennesi for their contribution and support.

[2] The common element in many definitions of non-performing loan relates to the borrowers’ failure to pay either the principal or interests. The key aspect is that the loan becomes non-performing if the borrower has failed to pay either the principal or interests over the last 90 days, as also indicated by the Basel Committee definitions. See P. Baudino, J. Orlandi and R. Zamil, The identification and measurement of non performing assets: a cross-country comparison, Financial Stability Institute (BIS), Insights on Policy Implementation N. 7, 2018.

[3] European Council, Council conclusions on non-performing loans in the banking sector, 11 July 2017.

[4] See the fourth Progress Report on the reduction of non-performing loans and further risk reduction in the Banking Union, 2019.

[5]See ECB, Communication on supervisory coverage expectations for NPEs, August 2019.

[6]See E. McCaul,Banks’ credit risk management and IFRS 9 provisioning during the Covid-19 crisis, Nov. 2021; see also ECB, FAQs on ECB supervisory measures in reaction to coronavirus.

[7] The harmonized criteria to identify NPLs are established under Art. 178 CRR, further specified by the Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/171 and the EBA Guidelines on disclosure of non-performing and forborne exposures (EBA/GL/2018/10). Going forward, the new draft Capital Requirements Regulation III which implements the latest modifications agreed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (Basel III+), currently negotiated by co-legislators, provides for a small and proportionate set of NPL disclosures by all banks (also those small and non complex).

[8]Regulation (EU) 2019/630 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards minimum loss coverage for non-performing exposures, OJEU, 25.04.2019.

[9] The calendar foresees the full coverage of non secured loans within three years at the latest, while secured loans must be fully covered within seven to nine years. See ECB-SSM: What are provisions and non-performing loan (NPL) coverage?The backstop applies only to loans originated after April 2019, earlier loans are subject to the SSM supervisory guidance, which is aligned with the backstop regulation. The ECB revised its supervisory expectations concerning prudential provisioning of new NPLs, aligning such expectations to the prudential backstop. The only differences relate to the legal nature of the two frameworks and their scope of application. The prudential backstop is binding (“Pillar 1”) for all banks in the European Union and applies to loans granted from 26 April 2019 onwards, while the ECB supervisory expectations are non-binding (“Pillar 2”) and apply to all loans, including those granted before that date.

[10] See the EBA Guidelines on management of non-performing and forborne exposures, 31.10.2018.

[11] The EU legislators provided targeted amendments to the securitisation regulation and the capital requirements regulation (CRR). Amendments to the securitisation regulation removed obstacles to NPL securitisations, including synthetic ones, while amendments to the CRR clarified how risk weighting should be calculated by banks securitising their distressed assets.

[12] Directive (EU) 2021/2167 of 24 November 2021 on credit servicers and credit purchasers and amending Directives 2008/48/EC and 2014/17/EU, OJEU, 8.12.2021.

[13] The template has mandatory data fields (more impactful for NPL evaluation, which banks should provide in data format) and non-mandatory data fields (which banks should make reasonable effort to provide in data format or, if not possible, in different formats).

[14]Commission staff working paper, European Platforms for Non-Performing Loans, 28.11.2018.

[15]European Commission, Tackling non-performing loans in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, 16.12.2020.

[16]The two conditions for an optimal employment of AMC were identified by the European Commission in its AMC blueprint, a staff working document to facilitate the establishment of AMC by Member States.

[17]At least 12 European countries, including the UK, used AMCs in those periods. See E. Avgouleas, R. Ayadi, M. Bodellini, B. Casu, WP De Groen and G. Ferri, Non-performing loans – new risks and policies ? What factors drive the performance of national asset management companies ?, Policy paper drafted for the European Parliament, 2021.

[18]See Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament, PublicHearing with A. Enria, Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, Brussels, 27.10.2020, where in light of the potential effects of the pandemic on loan asset quality he reiterated the proposal to address the NPLs problem with the creation of an European AMC or a network of national AMCs.

[19] Outside the limited exception offered by the “precautionary recapitalisation”, an higher price would be considered as an extraordinary public financial support according to art. 32 BRRD, triggering the resolution or the liquidation of the bank.

[20] EBA Risk Dashboard, Report on risks and vulnerabilities in the EU financial System, April 2023.

[21] Non-performing ratio is calculated including “cash balances at central banks and other demand deposits”.

[22]Under IFRS 9, impairment of loans is recognised in three different stages. This classification requires banks to monitor the change in credit risk over the life of their loans and compare this to the credit risk at initial recognition in order to determine the amount of provisions recognized. In determining whether a significant increase in credit risk has occurred since the initial recognition of a loan, a bank is to assess the change, if any, in the risk of default over the expected life of the exposure. The loans whose credit risk has not increased significantly are categorised as “stage 1 or performing” loans. A loan is classified as “stage 2” if its credit risk has increased significantly since initial recognition and is not considered impaired, whereas it is classified as “stage 3” if the loan’s credit risk increased to the point where it is considered credit-impaired.

Documents

Contact our communications team

Recent news